Suche

Siddhartha

E-Book (EPUB)

2023 Pushkin Press

160 Seiten

ISBN: 978-1-80533-020-2

in den Warenkorb

- EPUB sofort downloaden

Downloads sind nur in Österreich möglich! - Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als Taschenbuch erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

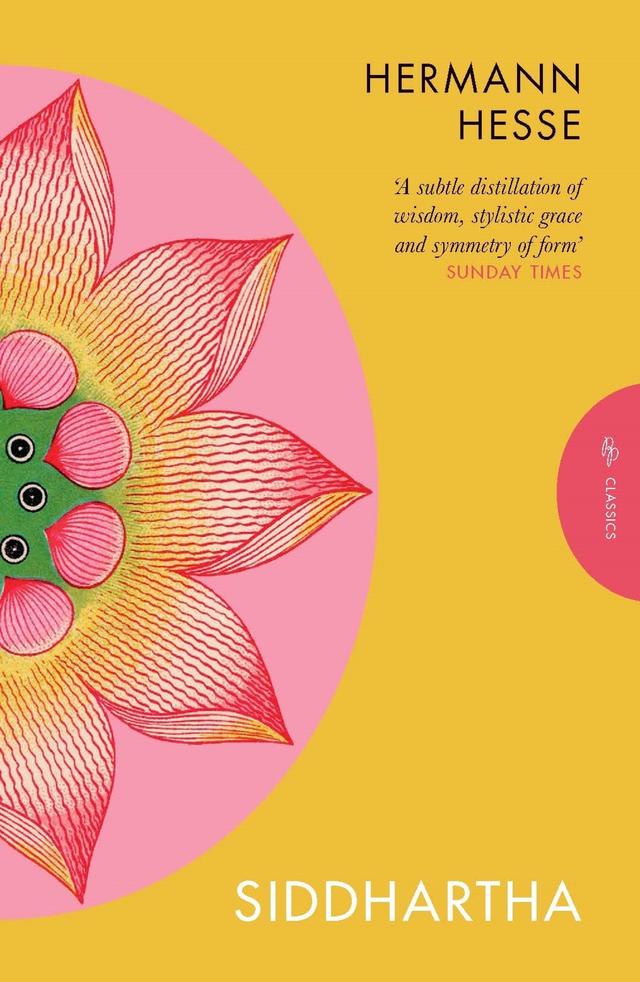

An inspirational classic from Nobel Prize-winner Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha is a beautiful tale of self-discovery 'A subtle distillation of wisdom, stylistic grace and symmetry of form' Sunday Times 'It's hard to think of a more recent novel that has sung so eloquently the joys of being alone' Guardian Dissatisfied with the ways of life he has experienced, Siddhartha, the handsome son of a Brahmin, leaves his family and his friend, Govinda, in search of a higher state of being. Having experienced the myriad forms of existence, from immense wealth and luxury to the pleasures of sensual and paternal love, Siddhartha finally settles down beside a river, where a humble ferryman teaches him his most valuable lesson yet. Hermann Hesse's short, elegant novel, echoing the life of the Buddha, has been cherished by readers for decades as an unforgettable spiritual primer. A tender and unforgettable moral allegory, it is an undeniable classic of modern literature. Part of the Pushkin Press Classics series: timeless storytelling by icons of literature, hand-picked from around the globe

Hermann Hesse (1877-1963) is counted among the leading novelists and thinkers of the twentieth century. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1946 for a body of literature renowned for its humanist, philosophical and spiritual insight. His most famous works include Siddhartha, Journey to the East, Demian, Steppenwolf, and Narcissus and Goldmund.

Beschreibung für Leser

Unterstützte Lesegerätegruppen: PC/MAC/eReader/Tablet

THE BEAUTY OF SIDDHARTHA'S WEAKNESSES

'I can think, I can wait, I can fast.' As an innocent fifteen-year-old, incarcerated in a fifteenth-century boarding-school in suburban Berkshire, I scribbled down those words upon my first encounter with Siddhartha and felt transformed. How could wisdom be at once so simply phrased, I thought, and yet so radical - so much deeper than everything I heard from my teachers or my parents? After many years of chapel I was trained to tune out any word that began with a capital letter, and I didn't have a clue what Hesse was going on about with all his talk of 'Brahmins' and 'the Illustrious One'. But something in the clarity and directness of Siddhartha's arrowed proclamation stirred me, spoke to a secret restlessness - and I didn't read closely enough to see that even that bold assertion will be undercut, as so many of Siddhartha's illuminations are, before the novel is over.

I'd already devoured Hesse's Narziss and Goldmund, a tale of a romantic adventurer and a monk that seemed made for us boys in our medieval monastic cells, longing for foreign places and girls. I had guessed that it was acceptable to read Hesse because he had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, and so seemed as legitimate as the Thomas Mann or Jean-Paul Sartre with which we precocious boys were so eager to impress one another. I knew, too, that Hesse's starting-point - that there must be something more to life than comfort and material possessions - had truth, since all of us were living in a luxurious sanctuary with its own secret gardens and rivers and Gutenberg Bible, and still we wanted to be out in the world, confounded.

What I didn't know - couldn't have accepted then - was that literally millions of others were thrilling to the same book across the world, in much the same way; to me - and this is part of Hesse's strength - it seemed the story of me alone, someone whose ideas and destiny were apart from those of the normal world. As a boy, I could not make out the complexity of the book, its suppleness and ease with paradox, and was in no position to discover how, for Hesse (a patient of Jung's while completing Siddhartha), his story was less about finding the light than about confronting the shadow and looking past a high-minded boy's ideas of being superior or apart. For a teenager, the novel touched the same hidden place as some of the simpler parables of D.H. Lawrence (The Virgin and the Gypsy, The Man Who Died), the questing ballads of Leonard Cohen, the novels we eagerly slipped one another under our desks, Le Grand Meaulnes and The Magus.

Those books that capture the world's imagination, at least as cosmic, universal fairy-tales - from The Little Prince to The Alchemist - depend for their power on a disarming combination of parable and complexity; they can be read by any kid, in other words ('age 14 and up' advises my edition of Siddhartha), but they're best savoured by someone who's known something of suffering and loss. They speak in several languages at once. As a boy, I was too young to follow most of the implications of Hesse's attack on 'spiritual materialism', as it's called, the sense of ambition and pride and self that lies even in the wish to be free of self; I couldn't see that his wisest line here might be that 'The wisdom which a wise man tries to communicate always sounds foolish.' I simply responded to the vague outlines of the tale, its sense of yearning. When I go back to it now it's the refusal to accept any answers and Siddhartha's final assertion that it's seeking itself that obscures the truth that impress me more with their unexpectedness. Inside the guise of a simple Eastern fable, Hesse is delivering an anguished German Bildungsroman about a young man who comes upon a new self-cancelling revelation every d