Suche

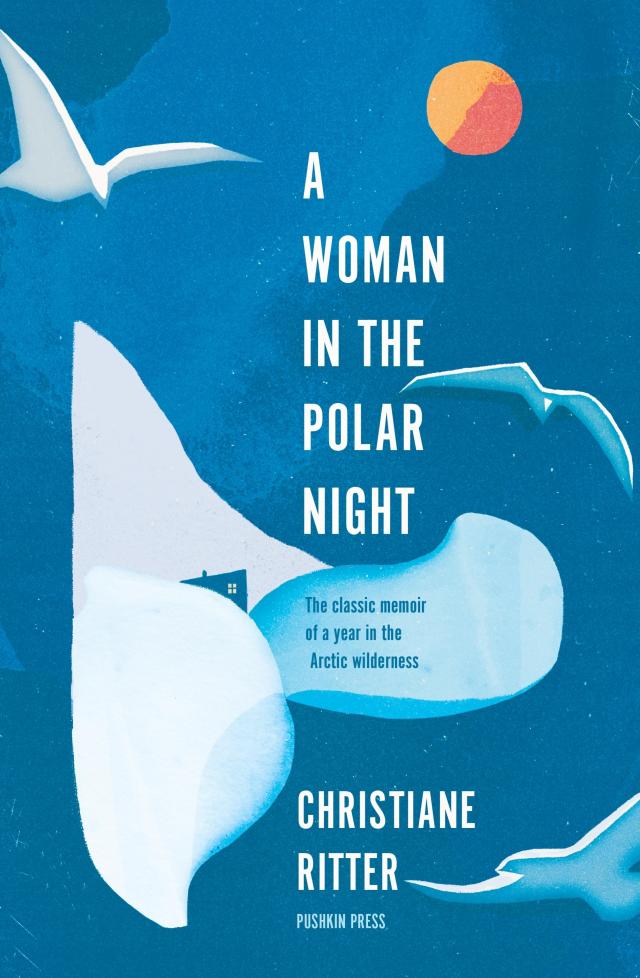

A Woman in the Polar Night

E-Book (EPUB)

2019 Pushkin Press

224 Seiten

ISBN: 978-1-78227-565-7

in den Warenkorb

- EPUB sofort downloaden

Downloads sind nur in Österreich möglich! - Als Taschenbuch erhältlich

- Als E-BOOK (EPUB) erhältlich

The rediscovered classic memoir - the mesmerizingly beautiful account of one woman's year spent living in a remote hut in the Arctic 'Conjures the rasp of the ski runner, the scent of burning blubber and the rippling iridescence of the Northern Lights' Sara Wheeler '[An] astonishing, haunting memoir' Isabella Tree In 1934, the painter Christiane Ritter leaves her comfortable home for a year with her husband on the Arctic island of Spitsbergen. On arrival she is shocked to realise that they are to live in a tiny ramshackle hut on the shores of a lonely fjord, hundreds of miles from the nearest settlement. At first, Christiane is horrified by the freezing cold, the bleak landscape and the lack of supplies... But after encounters with bears and seals, long treks over the ice and months of perpetual night, she finds herself falling in love with the Arctic's harsh, otherworldly beauty. This luminous classic memoir tells of her inspiring journey to freedom and fulfilment in the adventure of a lifetime.

Born in 1897, Christiane Ritter was an Austrian artist and author. She wrote A Woman in the Polar Night on her return to Austria from Spitsbergen in 1934. It has since become a classic of travel writing, never going out of print in German and being translated into seven other languages. Christiane Ritter died in Vienna in 2000 at the age of 103.

Beschreibung für Leser

Unterstützte Lesegerätegruppen: PC/MAC/eReader/Tablet

In these pages, first published in 1938, Christiane Ritter conjures the rasp of the ski runner, the scent of burning blubber and the rippling iridescence of the Northern Lights. Her prose is as pared as Arctic ice. As her adopted country languishes "in bluish grey shadow", the author discovers, with childlike delight, the uncluttered nature of life in the Norwegian Arctic, where "everything is concerned with simple being".

Ritter's husband Hermann had taken part in a scientific expedition in Spitsbergen and stayed on, fishing from his cutter in summer and in winter, when everything was frozen, hunting for furs. The Austrian Ritter, who was in her mid-thirties (she was born in 1897), did not follow at once, but when Hermann asked her to join him as "housewife" for a winter, she accepted. Before leaving home in 1933, she said that to her "the Arctic was just another word for freezing and forsaken solitude".

The reader does not know why Hermann had chosen to be absent from the family home for so long. The couple had a teenage daughter who is not mentioned in the book.

They live in a small hut at Grey Hook on the north coast of Spitsbergen; an amiable Norwegian hunter called Karl Nicholaisen joins them there. Their nearest neighbour, an old Swede, is in another hut sixty miles away (so "it won't be too lonely for you", Hermann wrote to his wife apparently without irony). The trio have supplies, but the two men must hunt if they are to survive.

Svalbard, Ritter explains, "is the old Norwegian name for Spitsbergen", and it means "Cold Coast". In fact, the archipelago, of which Ritter's island was the largest, had been renamed Svalbard a few years before the author's occupancy. Spitsbergen remains the official name of that one island, one of the world's northernmost inhabited places. Though it was barely inhabited in the author's day: early peoples never got that far after trekking east across the strait now called Bering and beyond.

First impressions are bleak.

The scene is comfortless. Far and wide not a tree or shrub; everything grey and bare and stony. The boundlessly broad foreland, a sea of stone, stones stretching up to the crumbling mountains and down to the crumbling shore, an arid picture of death and decay.

"A beast of a stove" leaves the hut coated in soot at all times, a state of affairs Hermann, fastidious in lower latitudes, calmly accepts. "How Spitsbergen has changed him," notes Ritter. She acknowledges "horror and dread", though doesn't tell her husband how she feels. When she arrives her eyes smart from unending daylight; then comes the long night, with its psychological challenges. She experiences rar, the Norwegian word for the strangeness that afflicts many who overwinter in the polar regions. All indigenous languages, such as Inuktitut, have a word for rar. Norwegian hunters apparently used to say ishavet kaller, or "the Arctic calls", when one of their comrades hurled himself into the sea for no reason. But the author's moments of despair are just that-momentary. Then she begins, maniacally, to sew, mend and polish.

Ritter has her own room in the hut (it is six feet by four, with an inch of ice on the walls), and sometimes moonlight filters green through the small snowed-up window. For a month the trio have a light cycle, during which they collect birch bark born on the tide for kindling, then darkness takes over: that chapter is called "The Earth Sinks into Shadow". Arctic foxes change colour, ptarmigans lose their spots, and everything freezes. I was in the polar regions once during the onset of winter. Night rolls in like a tide: it is one of the greatest seasonal events on the planet, akin to the rising of sap. (The author uses the adjective "titanic" three times to describe it.) In the smoky hut the trio play cards, thou